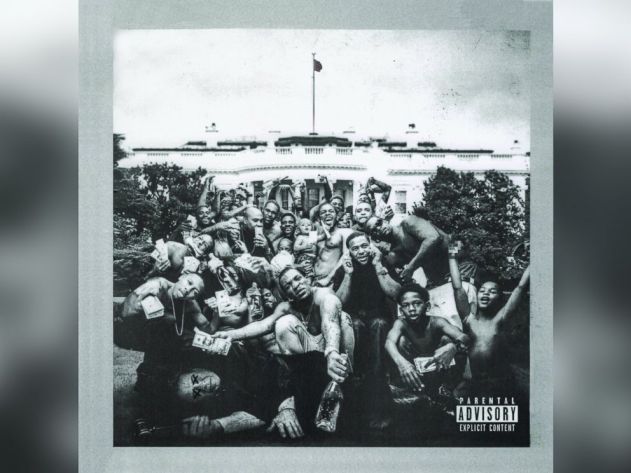

Unless you’ve been living in a hyper-productive, internetless void, you’ve noticed the instant, potentially blinded, adulation for Kendrick Lamar’s latest album, To Pimp a Butterfly. Begging the question, how is an album, and in a macro sense an artist, speaking from such a specific point-of-view attaining such incredible acclaim and far-reaching popularity? Now through five front-to-back listens, I’m ready to explore why this might be.

Is it the delivery?

The Beyonce-release, dropping an album unexpectedly without promotion or notice, is here to stay. It has shown to be a knockout success for Beyonce, D’Angelo, Drake and most recently for Kendrick. I don’t know about yours, but my timeline was congested with premature claims of TPAB being a classic album less than an hour from its release. The buzz generated by Kendrick Beyonceing his record can only be classified as a stroke of smooth marketing.

In a world of declining record sales, social buzz is the most valuable commodity a modern artist can possess, and this ploy gave Kendrick droves of it. Releasing the album on a dime gives the consumer an intimate connection with the artist, an immediate shared listening experience with social media at large. Not too mention the financial savings, far less advertising, this mode of delivery gives to the shrinking budgets of major labels. The drawbacks are minimal, the largest being that critics are forced to digest an album and publish a review in a window of about four hours, as opposed to their typical two weeks. But who reads reviews anymore? With streaming, the modern music consumer doesn’t need the music critic. They can listen to the album, for free, and gain their own impression before deciding to purchase the product—whereas in literature and film, customers utilize the critic to decide whether or not they should invest the money to discover their own opinion.

The success of TPAB benefits from the delivery, but it is not a sole reason. Kid Cudi made a release like this with his last album, and the response to that was chilly. It can’t be the release.

Is it a Good Kid, M.A.A.D City hangover?

Good Kid is universally, at least as much as possible in the Twitter era, considered to be a classic album. Released in the post-Drake Hip-Hop climate, Good Kid demonstrated a flawless blend of melody, storytelling, and novel vocal delivery. A concise, thematically-consistent 12-track sonic dream, the album was able to do what few can—shed out monster singles without jeopardizing the album’s individual artistry. Bitch Don’t Kill My Vibe, Swimming Pools, and Money Trees all charted tremendously on their own, yet the when they play in the natural flow of the album, they don’t sound like singles.

Is the urgency in awarding TPAB a classic tag a blinded reaction carried over from Good Kid? I think not.

In music, hip-hop specifically, following up a classic debut album is an impossible burden, not an unfair advantage. Just ask 50 Cent whose follow up to (one of the greatest debut albums in the infancy of hip-hop’s thirty-year history) Get Rich or Die Tryin, The Massacre, was received as a disappointment despite selling over a million records in its first week and receiving a Grammy nomination for Best Album—when Grammy’s were still something to be desired. Or Nas, who after 25 years of attempting to outrun the enormity of the success of his debut album Illmatic, capitulated and, in an unprecedented move, began to tour the quarter-century old record. When his acting jobs finally dry out, look for 50 Cent to do the same.

Though not a debut, Drake was also greeted with a less-than-tepid response for his Nothing Was the Same offering, following the classic-worthy Take Care. When your debut is a classic, we grade everything that follows on its Mt. Everest-level pedestal. So that isn’t the case here.

Is it the Messaging?

When you boil down the sharply structured, speed-variant verses, the Outkast-esque balance of hollow drums, bright horns, and myriad soul-infused backup vocals, TPAB is an album about survivors guilt. A continuation of Good Kid, where Kendrick voices the effects that the constant tugging of gang-culture had on the shaping and developing of himself as a man and an artist. On TPAB, he expresses the guilt and confusion for how he has became famous by narrating the inner-city plight for the consumption of White America.

But what makes the discourse of this album so interesting, and Kendrick in general, is that to Kendrick Lamar, there are two White America’s.

There is the White America who shot Trayvon Martin, who squeezed the life from Eric Garner, who failed to indict the killers of Tamir Rice and Michael Brown, who continue to harbor the nasty, archaic, diseased racism of our ignorant American predecessors. He takes aim at them on one of the album’s richest tracks, Blacker the Berry.

You hate me don’t you? You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture.

Kendrick calls these idiots out, and also rubs their faces with the fact that he, a symbol of their hate, is among the most important artists in popular culture. He is thumbing their noses in the fact that their way of thinking is endangered.

Endangering the racist philosophies of the White America of the past, is the other White America Kendrick Lamar recognizes: the growing class of antiracist whites within leftist White America — and they all seem to love Kendrick Lamar.

Open up a new tab and run a Google-image search of black lives matter.

Welcome back. You noticed it, didn’t you? Many of the images displayed young white Americans, protesting their exhaustion towards the continued mistreatment of black citizens by those entrusted to protect and serve them. Now remember your timeline during the Ferguson protests. Remember the beautiful cross-racial unity of users shouting their discontent for the happenings on their televisions, ashamed and sickened by the actions committed by those of their race in their country. If nothing else, Ferguson showed America that its youth are invested in bettering their future and are unafraid of applying pressure upon their own community: that they are determined to eradicate the racial injustice amidst its community.

Kendrick is aware that a majority of his fans are of this demographic. Though confused by it, he can’t help but notice them at his concerts, or heaping praise upon his Twitter feed.

For a twenty-something white person from the middle class, there is very little to relate to on TPAB. Generally speaking, a majority of people listen to a particular artist because of their relatability to the content. We like Taylor Swift because we’ve all experienced rejection, as she claims to have in her songs. It’s essential that Drake fans know that he is just like them: insecure, introspective, and over-expressive —though of course Drake is a hyper-wealthy, limitlessly famous and ultra-talented version of ourselves. We identify with 2015’s biggest anthem, Know Yourself, because we can envision ourselves having everything, yet still being overwhelmed with stress and longing.

But Kendrick doesn’t cater to his white fans, like his peers do, instead he detours them into his Compton upbringing. As evidence by Hood Politics. A song that features in its chorus the line:

We was in the hood, 14 with the deuce deuce.

This growing element of socially-aware White America doesn’t know a damn thing about being 14-years old, strapped with a pistol. We don’t know anything about Sherm Sticks. Most hadn’t a clue who King Kunta was before hearing Kendricks masterful track. He even nodded to this ignorance by interpolating the Seinfeld theme song, a show that I love, but lets face it, pretty much ignores black people. But the incredible acclaim and far-reaching popularity of this album shows us is that we don’t have to relate to an experience to enjoy and appreciate it.

To Pimp a Butterfly forces the white listener to experience a new, under-served perspective. It forces the white listener to take inventory in their own stereotypes, as Kendrick takes inventory of himself on the introspective, unconventional jam-track “U”. Kendrick questions whether he is doing enough for the betterment of his people. At the same time the white listener examines themselves, realizing that just because you tweet that #BlackLivesMatter doesn’t mean you, the tweeter, are doing enough. But its the recognition of the problem that is the true triumph by Kendrick, and the listener.

We, as a society, still have a long road to defeating racism. Racism is not merely an age thing, as evidenced with the Oklahoma frat scandal last week. But the fact that one of the fraternity brothers recognized the necessity for this hate-filled nonsense to be exposed by filming and leaking the video, shows progress. The pop-level popularity of To Pimp a Butterfly is proof that there is reason to be optimistic about America’s social future.

And that is why we love Kendrick Lamar. That is why we shower him with well-deserved praise.