I’ve recently published several short story/ flash fiction pieces. You can read those by clicking the links below.

Unmasking the Cult of Stephen Curry and the 2016 Finals

The Cult of Steph Curry is a ferocious horde—a Twitter-dwelling echo chamber, armed with crying-Jordan memes and next-gen stats, as passionately intent on spreading the myths of their prophet as Beyonce’s social-media army. The platitudes they spit out about Curry, and the record setting 73-win juggernaut he plays for, are easy to rally behind. Home grown. Underdog. Organic. Skill based. The right way. Do those sound familiar? They should.

Steph Curry broke onto the consciousness as a scrawny guard wearing a loose-fitting scarlet jersey repping a team you’ve never heard of. Call it fearless, call it reckless, Curry was launching twenty-five footers at a rare and disorienting rate. Before the analytic-driven revolution that led to the NBA spreading the floor and shooting more threes in the past three seasons than it did the previous eight combined, Steph Curry was throwing up ten threes a game. His collegiate star was brightest his sophomore year as he led his tenth-seeded Davidson Wildcats on an improbable Elite-Eight run, tallying 33 points per game and firing off 51 threes in four games. But the Steph Curry Cult wasn’t much more than a clamoring minority then. A legion of fans who loved showcasing him in March Madness 2009 (RIP to that terrific franchise) and a handful of others seduced by his boyish looks and limitless range. When he left Davidson and entered the NBA draft in 2009, he fell to seventh overall. Shoe companies didn’t line up to make him the face of their brand. ESPN didn’t play Warrior games, despite it’s large market. After his rookie season, his jersey wasn’t among the top 15 in sales. A top 15 that featured Nate Robinson and David Lee. No, he wouldn’t find himself on that list until 2014-15.

Curry got plenty of playing time during his rookie season, notching 36 minutes per game, but he seemed different from the energetic spark plug we saw in college. Was the physicality of the NBA overwealming? Did the Warriors coaching staff install a Governor on his shot selection? (He shot only four threes a game his first three seasons.) Then came the injuries. A bum ankle restricted him to only 26 games in the 2011-12 season. Due to the injury concerns, at the start of the 2012 season Curry signed a tepid four-year contract for $44 million. Where was his cult?

The answer resided in the sunny beaches of Miami.

Even before LeBron James infamously left Cleveland, a team that history often forgets was co-piloted by Mo-fucking Williams, a gang of idolatry Michael-Jordan worshippers snuffed out a threat and seized. Protecting their precious nostalgia, they tried to undermine LeBron’s every accomplishment and condemned his move to Miami. All of his achievements were qualified with a yeah but—he took the easy route, he needed Wade and Bosh to win, the East sucks. Yadda Yadda. Skip Bayless and the executives of ESPN seized on the fervor and built a race-baiting daytime empire around it. They did whatever they had to in order to protect the myth of Michael Jordan.

When attacking LeBron they ignored the seven-year Finals drought that Jordan suffered to begin his career, that he didn’t win until the Bulls drafted Pippen. When that tired, the LeBron dissenters elevated false champions. They clamored for Derrick Rose. So much so that the media, party to the LeBron nit-picking, flagrantly awarded Rose an MVP. When LeBron, and flimsy knees, set fire to the Rose effigy, they moved to Durant. But the lanky sharp-shooting seven-footer lost to LeBron in 5 and then couldn’t get back, despite having an supremely-talented alien for a sidekick in Russell Westbrook. The salt-ridden mass of LeBron haters had nothing to cling to.

Then a life raft emerged in the form of wide-grinned, shot-chucking Steph Curry.

Starting last year, people began propping up Curry over LeBron. It was bewildering and sudden and only intensified this season. Soon after, the Horde hopped over LeBron and started comparing Curry to Michael Jordan. Which is fine. Except none of the LeBron qualifiers existed. LeBron, who throughout his Heat run guarded the opposing team’s best player, in one Finals run guarding Paul George, Derrick Rose and Tim Duncan in successive series, would get ripped to shreds for a missed free throw and for missing half a Finals game with severe cramps. Whereas Curry, who was being hidden on opposing team’s worst offensive player, isn’t knocked for similar feats. Not for getting inarguably outplayed by Russell Westbrook, for getting injured, for relying on Klay Thompson’s heroic Game 6 performance to save their season. When has LeBron ever needed that? Don’t give me the Ray Allen shot unless you’re willing to strip away Jordan’s ring that Steve Kerr’s game winner secured. The one time LeBron was outplayed, by Kawhi Leonard in the 2014 finals, he was torn apart. And even that is arguable when you review the stats. While Curry was the fourth, maybe fifth, best player in the OKC Series, having two MVP-level games. 2-5.

Maybe you enjoy the horde. Maybe you are one of them. Maybe you dismiss the unbalanced math, 11.2 3PA’s per game this season, and raise up Curry’s numbers as evidence of his superiority to LeBron. Maybe it’s easier not to account for defense. Maybe you dismiss Klay Thompson the way you dismissed Scottie Pippen and the way you didn’t to Dwyane Wade—as a superstar and vital element of the myth-building. Maybe that’s ok. Maybe it’s just easier to give Curry all the credit. Maybe he’s less threatening to your Jordan nostalgia than LeBron is. Maybe it’s easier to pretend that Curry isn’t your anti-LeBron life raft.

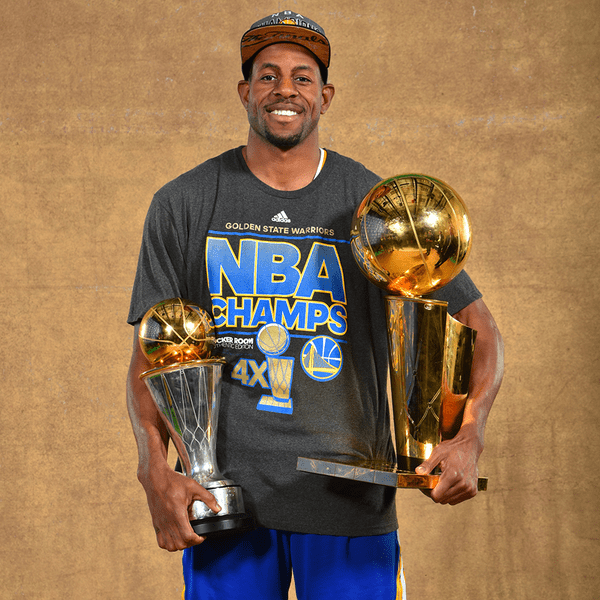

That Andre Iguodala wasn’t awarded the MVP for holding LeBron James to an astronomic 36-13-9 Finals line a year ago.

Finals Preview

It doesn’t matter how intently the Cavaliers staff breaks down the Thunder-Warriors game tape, they won’t be able to replicate the success that the Thunder had. At least not in the same way. Cleveland lacks the length and athleticism to do so. In one of the more surprising twists in the playoffs, the Thunder found success by playing at the high-flying pace of the Warriors. The Cavs can’t play like that.

On paper the matchup is lopsided. The Cavs have only one two-way player, LeBron, maybe two when Shumpert is hitting shots, where the Warriors have three—Thompson, Iggy and Draymond. Golden State can rotate Iggy, Barnes and Green on LeBron as they did last year and have Klay take Kyrie. Conversely, the Cavs will stagger Shumpert and Delly, neither of whom offer much offensively, on Curry and then pray that J.R. Smith can contain Klay. The latter is potentially the most troublesome matchup. Maybe they throw LeBron on him and rely on Love and Kyrie to carry the load offensively.

Much is being made about how the Cavs will hide Kyrie and Love on defense. Some say stagger them, some say play Frye over Love and Delly over Kyrie. Those suggestions seem to neglect that we saw a similar build last year and the Cavs fell in 6—against a Warriors team who is drastically improved this year. Though it will lead to frustrating Warrior runs, the Cavs can’t overly concern themselves with the defensive output of Love and Irving. If they revert to their turnstile selves, the Cavs have no chance of stopping Golden State. No matter what they do, Golden State will use pindowns to get Love isolated on Steph and Klay. Where it could get really ugly is if they can get Curry and Green pick and roll being guarded by Love and Irving. However, if they play Delly and Frye thirty minutes a game they have no chance at outscoring Golden State. So you have to play Love and Kyrie.

Lue will have to be creative with how he manages his rotation, but look for the Cavs to close games with Irving, Smith, Lebron, Love and Frye. That lineup has scorched the East during these playoffs, and, in terms of length, conceivably can guard the Curry, Iggy, Klay, Barnes, Green lineup the Warriors are likely to close with. Kyrie has demonstrated in fleeting moments throughout his career an ability to play average defense. Last year in Game 1, before blowing out his knee in overtime, he played Curry to a draw.

Can Kyrie play Curry to a draw a few times this series? Certainly. We just saw Russell Westbrook outplay Curry for an entire series and Damian Lillard come close before that. LeBron can match the Klay production, and Love and J.R. can match the output by Iggy, Draymond and Barnes—especially if Barnes looks the way he has. Remember that Cleveland had a 2-1 lead a year ago, then Iggy and Klay got hot and the rest was history.

The Cavs can pull off what would be the greatest Finals upset since the Dallas Mavericks beat LeBron’s Miami Heat in 2011. A result that the current occupants of the Steph Curry Life Raft love to throw. The annoying horde will be excited to fling 2-5 in LeBron’s face if the Cavs fall. They won’t remember that his team’s were underdogs in all but three of them—of which he’s 2-1. They won’t remember that Jordan’s teams were never an underdog. Or that if Steph and the Warriors repeat, they’ll do so as two-to-one favorites each time.

But go ahead, Curry Cult. Keep saying that your team, with two second-generation NBA players, came from the bottom and are underdogs. Whatever best feeds your myth.

Cleveland take game one, and wins in 6.

The Evolution of the Best Picture Nomination

Hollywood’s elite will gather at the Dolby Theater in Los Angeles to celebrate the 88th on Sunday. Much of the discourse surrounding the Oscars this year has been focused, deservedly so, around the glaring whiteness in the acting nominations. Before you dismiss this year’s show entirely, you should take notice of an evolution of the Academy Awards’ highest honor, the Best Picture category.

Though it’s not a perfect model, a reliable barometer to gauge the American public’s approval for a film is by its box office numbers. The more money the film makes, the more the public enjoyed it. (Or, the harder it was to ignore.)

Equally imperfect, a film’s artistic quality is determined by how it performs during award season. Typically, these two measures clash as the films that are nominated for Best Picture often go largely unseen by the American public.

Oscar-nominated films don’t fetch much attention at the box office because of their content, release date, and MPAA ratings, but it’s arguable that the film’s budget plays a role too.

Without a large-scale budget to allocate to distribution and marketing, many people will never hear about a film, let alone see it. In the past this has been the case with many Best Picture winners, including 12 Years a Slave (2014), The Artist (2012), Hurt Locker (2010), and Slumdog Millionaire (2009). It’s especially true with some of the nominees: Philomena (2014) Armour (2013),The Tree of Life (2012), Winter’s Bone (2011), The Kids Are All Right (2011), Milk (2009), and The Queen (2007).

Average Film Budget By Best Picture Nomination Class

2013: $52.1M

2014: $39.7M

2015: $19.6

2016: $70.1M

In recent years, however, that trend seems to be changing. Movies with larger budgets are getting nominated. Never more so than in this year’s class of Best Picture nominees. This past year saw a number of big-budget films that were each able to both rake in box-office bucks and receive critical approval: Mad Max Fury Road, Jurassic World, Creed, The Revenant, The Martian, and Star Wars the Force Awakens . Each of those films received favorable reviews and cleared over $110M at the box office. In 2014 the year’s highest grossing film was American Sniper, which received a Best Picture nod.

The Academy is also becoming less snobby. Last year featured a pivotal change to convention when The Grand Budapest Hotel was nominated, despite being released in March. Typically the Best Picture nominees are restricted to a fourth-quarter release. A similar feat occurred this year with Mad Max Fury Road , which was released in May.

A third factor could be the Academy Awards as a broadcast property. In an unstable television landscape, threatened by cable cutting and streaming, the most valuable commodity for networks to possess is live-event programming. Sports, awards shows and political debates are among the most viewed programs. Is it possible that the Academy is intentionally nominating films that have registered large box-office hauls in order to increase viewership? Perhaps. Last year with a group of Best Picture nominees that featured lower-than-average budgets the show saw a major dip in ratings. A cynical mind might leap to a conclusion there.

No matter how or why it occurred, the 2016 Best Picture nominees break from convention. Whether or not this is an outlier or the beginning of an Oscar Evolution remains to be seen.

Will the big-budget trend of the 2016 Oscars contribute to big ratings and a more enjoyable show? Will Chris Rock hold Hollywood and the Academy’s feet to the fire? Will Leonardo DiCaprio pretend that he’s surprised to win Best Actor? Tune in Sunday night at 7:00 E/T on ABC to find out.

LeBron James, Underdog.

Since bursting into the national consciousness in 2001, LeBron James has been anything but an underdog.

A teenaged phenom from Akron, Ohio with boyish looks and grown-man game, LeBron James became the obsession of American sports. With a magnitude of national interest never before witnessed or approached since, the trivial high school games of a 16-year old kid became appointment viewing. Draped in his unprecedentedly popular and recognizable wide-cut number twenty-three Saint Mary’s jersey, tattoos obstructed by white bandages, a wide-smiling explosion of swaggering confidence, adolescent James dazzled America as he blew past and jumped over his competition, displaying a physical prowess never before seen at his age. Unlike the laundry list of child stars American culture had, and continues to, whittled down with over exposure and heaps of unobtainable pressure, LeBron didn’t crack under the nation’s microscope.

No, he embraced scrutiny by weaving it into motivation.

He dealt with the trappings of being uber-famous with unmatched and matured grace. He brushed off the infamous silver Hummer controversy and the throwback jersey farce, managed to remain focused and driven despite the bidding war of shoe companies that culminated with James signing a $90M contract before bouncing a NBA ball. Finally the lottery balls were plucked, and the two-year certainty that LeBron James was to be the 2003 first-overall draft pick became a reality. His Cavaliers premiere, an irrelevant October road game, was as anticipated as a regal coronation—one befitting of his nickname, King James.

Rare is it for hype to be met, more rare is it to be exceeded.

An element that has amplified the enjoyment of experiencing LeBron’s career has been the divisive discourse examining his every sentence, shot, or non-shot. It seemed everyone found themselves entrenched in two specific and equally illogical camps. Both supporters and dissidents displayed a severe patience deficiency. Every win LeBron mounted was evidence of his greatness, each loss a nail in the he-isn’t-Jordan coffin. Both sides of the debate were wrong, as they each were measuring the accumulation of snow before the storm was over.

LeBron’s storm continues. It has spanned twelve years, eleven All-Star games, four MVP’s, two championship rings and numerous iconic performances. No matter which side of LeBron James public opinion spectrum you reside, the Chosen One’s greatness has achieved bipartisan consensus, even from the stubborn cul-de-sac’s of Kobe Bryant sycophants or the staunch corners of Jordan stalwarts. What remains of the debate is the degree of his greatness.

The 2015 Finals are already being built as a Litmus test, an opportunity for LeBron to further his greatness. Though he won’t admit it, his Cavaliers are significant underdogs entering their showdown with Golden State.

According to Vegas, if Cleveland were to win the Finals this year they would be the greatest underdog to win since the Detroit Pistons toppled the Lakers in 2004. After securing his fifth consecutive Eastern Conference Finals, while dragging a mediocre cast that featured three Zombie-Knicks, an undrafted point guard, and a one-way floor-spacer who was deemed too long-of-tooth to garner a single minute in the 2011 NBA Finals, and a head coach who doesn’t actually coach, LeBron has been receiving appropriate recognition for his already impressive and unexpected achievement.

Considering the steep odds, is it fair for the result to shift the narrative in the other direction? Would a loss detract from LeBron’s greatness?

In sports, we wrongly compartmentalize history by only preserving the surface result. We disregard the minutiae, and the wealth of commentary it provides. Fossilized in time is the push-off game-winner Jordan hit in the 1998 Finals. Deleted from record is the inefficient 15-35 Jordan shot in that pivotal game. We rarely account for the events and the circumstances that rendered the result.

Below are two accumulated stat lines from a NBA Finals series.

Player A: 28.6 PPG; 8 RPG; 3.9 APG; 2.1 SPG; 40% FG.

Player B: 28.2 PPG; 7.8 RPG; 4.5 APG; 1.7 SPG; 57.1% FG.

Looking at the two lines, Player B is quickly discerned to be the better Finals performance considering significant advantage in efficiency. Yet, history remembers Player B as coming up short, whereas Player A’s performance is showered in roses.

Player A is Kobe Bryant during the 2010 Finals. Player B is LeBron in the 2014 Finals.

We fail to examine losing as binary the equation it is. We don’t say, “Tom Brady and the Patriots lost the 2007 Super Bowl, but….” We say Brady and the Pats lost, they’re overrated and everything else becomes tertiary. Even though the 2007 Patriots are one of the greatest teams in NFL history, we disregard them as overrated.

In real time, LeBron’s 2007 overmatched Cavs were celebrated for winning the East and securing a Title birth. Little criticism was heaped at the 22-year old LeBron when they were dismantled by the far more talented Spurs. The time-proven doctrine that hero ball had never, and will never, succeed at the NBA’s highest pedestal was offered as LeBron’s hall pass. The failure wasn’t his, but that of his front office.

Yet, over time, the public lost perspective. They forgot that the 2007 runner-up’s second best player was Drew Gooden. They forgot what it looked like when time after time Zydrunas Ilgauskas leaped off balance after Tim Duncan pump fakes, or how easily Tony Parker drove past Boobie Gibson, and how grotesque it was to see Sasha Pavlovic guard a full-haired, quick-stepped Manu Ginobili. Time boiled down the series to its final result: LeBron got swept.

Finals Preview

The 2015 Finals will be decided by how each team assigns defensive matchups, and how they counter those assignments with subsequent strategic adjustments. The deadliest weapon in the Golden State’s armory isn’t their three-point shooting, their drop-of-a-dime runs, or even their possession of two league’s most dangerous heat-check threats. No, Golden State’s power punch is their defensive flexibility.

The top-ranked defensive unit in terms of efficiency this season has numerous options to defend the League’s best player. They will likely start Harrison Barnes on LeBron, with the instruction to drop below screens and to give LeBron the perimeter jumpers he has struggled with this postseason—he is just 33% on long 2’s and 17.6% on 3’s this postseason. If he finds his jumper, they will throw Draymond at him and live with the consequences of Tristan Thompson snagging offensive boards over the smaller Barnes or the slower Bogut. All the while, they blanket Klay on Kyrie, if he’s playing effectively. If he’s hobbled and forced into a Mike Miller stand-in-the-corner role, they have Klay chase J.R. Smith around.

On the other end of the court, Cleveland will likely throw Shumpert on Curry, who has the length and quickness to contain the MVP. Golden State will employ a flurry of Thompson, Green and Bogut picks at Shumpert, hoping for a switch that leaves Curry on an island with Irving, Thompson or Mosgov guarding him. Each of those scenarios are grim for Cleveland. When healthy Irving is a liability on defense, when slowed by injury he becomes as abhorrent defensively as Steve Nash.

I see only two roads to victory for Cleveland, and both are as claustrophobic as the alleyways of Sarajevo.

The first and most unlikely road is that LeBron disproves the time-proven doctrine that hero ball can’t win a title by offering four game-six-in-Boston performances. He does what Allen Iverson did in Game 1 of the 2001 Finals, only four times over. To do this he would need to find his lost jumper, return to his Miami Heat efficiency, and erase either Klay or Steph’s offensive output on the other end. And that still might not be enough.

The second and more travel-friendly road is to get Draymond Green in foul trouble. Largely consequence of limited exposure from playing in the Pacific Time Zone, the debate on whether Draymond Green would get a max contract this coming offseason was a fun conversation to entertain. Traditionally he would be a role player, but his skill-set is tailor made for the style of basketball being played today. If he hadn’t already asserted himself as a top-15 player, these playoffs have cemented Green as such, and eliminated the conversation of warranting a max contract. That is now a point of fact. The secret is out on Steve Kerr’s Swiss Army knife, and calling him underrated has become an erroneous statement. Green is the V-8 engine which drives the daunting Golden State defense. His ability to stymie bigs and guards alike is as valuable to the Warriors as Steph Curry’s lighting-quick release.

To get Green in foul trouble, Cleveland will have to employ the staple of the their opponents offense: movement and on-ball pick and rolls. LeBron’s band of misfit toys have rarely utilized P&R’s this season. Their primary offensive action is for LeBron to absorb defenders and kick out to open shooters, which as far as stretching a definition goes, is analogous to calling Rick Perry a liable presidential candidate or Iggy Azaela a musician.

If Cleveland trots out this archaic offensive approach, Golden State will make quick work of the series. They will simply sag off LeBron, drape Cleveland’s perimeter shooters, and dare LeBron to beat them by shooting 35 times a game. The most effective way to minimize LeBron is to take away his assists.

However, if Cleveland evolves and deploys LeBron-Thompson P&R’s and collects early fouls on Green, they stand a chance. If Cleveland can dispatch Green to wave towels with David Lee on the Warriors bench, they force the Golden State to play Bogut-Barnes-Iggy/Livingston-Klay-Curry units, which allows for Cleveland to stash the hobbled and defensively-adverse Kyrie Irving on Iggy/Livingston. Offensively, it forces Barnes and/or Klay Thompson to attempt to fight over Mosgov pick-and-dives, in fear that LeBron will have Bogut switched onto him.

If Cleveland can couple a few games of Green in foul trouble with LeBron super-stud games, they shorten the talent gulf between the two teams. If they can’t, we’ll see the impossibly-adorable Riley Curry Schmoney dancing onstage as Commissioner Silver awards the Warriors the Larry O’Brien trophy.

Aftermath

No matter how well LeBron plays in the 2015 Finals, if Cleveland loses, the immediate response will be negative. Twitter will overdose on memes of Kermit drinking tea, only with Wade and Pat Riley and Michael Jordan’s heads photoshopped in place of the Muppets character. Analysts will be quick to remind audiences that Jordan never lost in the finals. Skip Bayless will arrive to the First Take set fully erect, ready to shout 2-and-4 from the vaulted and, unfortunately, persuasive ESPN mountaintops. The defunct LeBron-isn’t-clutch narrative will be dredged back up, despite the litany of evidence dismissing its merits.

History will not remember the insurmountable odds that beset them. We won’t remember that LeBron wasn’t supposed to reach the the Finals this soon. History will likely forget that J.R. Smith was his second best player and will almost certainly misremember how hobbled Kyrie was—that three of the Cavs four highest paid players were injured. We won’t credit Golden State as the juggernaut that they rightfully are.

We might even forget that the 2015 season was the first time in NBA history that a player commanded full control of a NBA franchise, dictating coaching and front offices decisions alike.

Hopefully my fears will be unfounded. Perhaps history will act outside of its nature and the surface result won’t cannibalize the narrative. Perhaps it will honor LeBron’s 2015 campaign the way it has honored Allen Iverson’s 2001 march to the Finals. Not a title, but as impressive a defeat as there is. But more than likely, history will treat it like it did Dwight Howard in 2009, LeBron in 2007, Dirk in 2006, Reggie Miller in 2000, and Shaq and Penny in 1995: as nothing more than a failure.

What a shame that would be.

The Less-Than Super State of Superhero Films

In the coming weeks Marvel will spit out their latest Avengers installment to kick off the summer blockbuster season. Age of Ultron will almost certainly gross a billion dollars worldwide, as its predecessor did. Unfortunately, film’s box-office success will only distance audiences further from an aesthetically variant, and refreshing, release and continue to perpetuate the genre’s stale storytelling habits.

We can trace the origins of the Superhero boom to Sam Raimi’s Spiderman in 2002 as the glossy visual effects and sly vulnerability of Tobey Maguire formed a delightful marriage for both comic book sycophants and general movie-goers alike. It was an above-average blockbuster, featuring a dapper young James Franco, not-quite-over-the hill Willem Dafoe and, most memorably, a bona-fide classic moment of romance with a gravity-defying kiss that EVERYONE has since duplicated poorly by hanging off the back of a sofa drooping down towards a lover in sloppy, tongue-confused imitation. The droves of ticket-buying viewers—the film grossed $821M, for context X-Men did $275M in 2000 and Batman and Robin did $238M in 1997— informed Hollywood that the market for comic-book adaptations was robust.

The result? Since Spiderman there has been forty-four comic-book Superhero blockbusters released, thirty-five coming from the Marvel universe alone. And that is excluding the litters of non Marvel and DC franchises such as Wanted, Jumper, Zorro, Hancock, Green Hornet, and the hoard of Michael Bay offerings.

There is nothing wrong with the superhero explosion at face-value. Hollywood, if anything, has mastered the skill of exploiting market trends with rapacious zeal. The issue is that so few of the films are manufacturing any cinematic or storytelling nuance. They are simply recycling the uninspired tropes of their predecessors while pandering to the faithful legions of readers of the particular comic book the films are adapted from. Worse yet, audiences are still flocking to see them, which leaves Hollywood erect at the prospective profits and aggressive in their coming releases.

Audiences, not Hollywood, can alter this spiraling trend of mediocrity. It is us that have the power. We can simply not see the films. Not surrender our hard earned twelve dollars to watch a series of CGI-enhanced explosions and a desultory storylines with their astonishing tension deficiencies.

There are three cliches that are chiefly responsible for subverting the genre.

The first, and most offensive, belabored recurrence in recent superhero films is the metropolitan showdown. Hollywood, without much difficulty, took notice of 9/11, realizing that the deepest image stained into the minds of every American of mental coherence at the time of that tragic day is that of metropolitan destruction. Borrowing from the horror genre, Superhero films can’t help but exploit America’s deeply-rooted paranoia of ruined skylines. So they lay waste to New York or Los Angeles or a faux New York or faux Los Angeles, in a 9/11 fashion at the climax of their films. Sometimes they’ll destroy Chicago in a hollow attempt at creativity.

It’s ready-made tension that is less authentic than the butter drenching the popcorn we shovel into our months while watching the languorous films. If you’re still awake for the ending of Man of Steel, you’re watching him bash skyscrapers through the filter of having seen, in real life, planes crash in the World Trade Center’s. The hatred and pain you experienced that morning is now in the theater with you, masking the lack of hatred and pain the film has provoked from you. See also Avengers, Star Trek Into Darkness, Pacific Rim, Godzilla, GI Joe, and, once more, the hoard of Michael Bay turds. It’s safe to assume the new Avengers movie will feature aliens causing havoc to some skyscrapers.

Wouldn’t it be refreshing to see a climax where buildings aren’t destroyed? One that is layered instead with the emotional collateral of the characters rather than the pre-existent emotional collateral of the audience watching the film?

Second, Make It Darker DAMNIT!

Christopher Nolan’s growling-voiced Batman took the stage in 2005 with the release of Batman Begins. It, and its two sequel counterparts, are conservatively among the best superhero comic-book adaptations to be released in the post-Spiderman bubble. However, the trilogy is also directly responsible for hindering creativity within its own genre.

Furthering the dark tone established in Tim Burton’s Batman, Nolan’s films pair the dark, brooding Bruce Wayne with poorly-lit scenes of emotional severity. This is especially true in Begins, which plays as if it was stricken with a lackluster lighting budget. Once Nolan’s The Dark Knight hit the box-office stratosphere and was bathed in critical acclaim, the leach-like copycats of Hollywood took notice. Since, most comic-book adaptations have poorly mimicked Nolan’s lighting deficiencies, disregarding the source of the darkness: Bruce Wayne’s character. That’s why Spiderman 3 looked like this, and why Man of Steel sucked the light out of the film and attempted to deceive audiences by placing Nolan’s name on the poster twice, despite his minimal involvement in the project. Similar antics are evident in Marvel’s Thor, Captain America and Iron Man films.

Then, last week, appearing to finally over dose on the make-it-darkernote, Warner Brothers belched out this atrocious trailer. Hey, we keep making shitty Superman movies, so how about we have him punch Batman a few times? We’re moving closer and closer to a reality that features a movie entirely black, its only lights the intermittent flashes of explosions and gun shots over a dark Hans Zimmer score?

Lack of Human Characters

This cliche is most relevant in Marvel films. We are never introduced to the countless mortals who inhabit the spectacular worlds of immortal heroes. And don’t tell me that Tony Stark acts as a human—or worse yet Gwyneth Paltrow’s wet blanket character whose sole purpose in the films is to serve the needs of Tony, an unfortunate example of the Hollywood’s tiresome construct of writing female characters who exist either as objects to be sexed by the protagonist or as erratic roadblocks coming between the protagonist’s desire. But that is an entire essay of itself…or five. In most Superhero films, there are only the heroes and the villains. The only humans we get are the stiff, undeveloped sexual objects of the heroes, or the brief cameos of children or animals acting as tension props.

Take Avengers for example. When the alien invaders are laying siege to New York and the Hulk is battering though skyscrapers, there are no stakes. We haven’t met the people who work in the skyscrapers. We don’t know about their families at home, watching their televisions horrified for their well being. Isn’t that why we were all hypnotized by our televisions during 9/11? The empathy that the people burning in the inflamed buildings were somebody’s parents, someones siblings? Why couldn’t Joss Whedon (director of Avengers) thread in a b-plot of a single-mother accountant working in one of the buildings destroyed during the film’s climax? Why not show her and her co-workers grappling with the dilemma of whether or not they should leap out of the collapsing building, instead of the alternative of burning alive? You could still have Iron Man fly in and save them before they meet the pavement, their certain death.

There is a glimmer of good news, however.

They’re few, but we’re getting some indication that a talented minority within Hollywood have grown weary of these redundant beats. Netflix recently dumped the entire first season of the delightfully-violent Daredevil. The show, though taking place largely in the darkly-lit corners of New York much like Nolan’s Batman Trilogy, features astounding cinematic achievement such as glorious one-take scenes such as this.

It features actual human beings who are forced to suffer the consequences of Matthew Murdock’s masked Vigilantism— specific examples being the well-written and delivered Rosario Dawson character and the affable Foggy Nelson. Last summer we were treated to some much-desired lighting with the shining release of Guardians of the Galaxy. Also, there were moments of humanity in Iron Man 3 with the little boy who helps Tony rebuild his suit and the terrific Ben Kingsley character. But the pleasantry is quickly forgotten as the film digresses into its ending, a conflagration of destructive explosions.

Then theres the new Star Wars trailer displaying a shipwrecked star destroyer. A reminder that while the Ewoks were getting turnt-up and drumming on the helmets of stormtroopers, others in the galaxy were left to clean up the mess.

There is lots of work to be done, as for every promising release like Daredevil and Guardians is countered by an overwhelming vomitorium of uninspired Zach Snyder films and Michael Bay catastrophes. But the encouraging news is that the audience can protest their upheaval and demand more from Hollywood. They can be heard by staying home this summer.

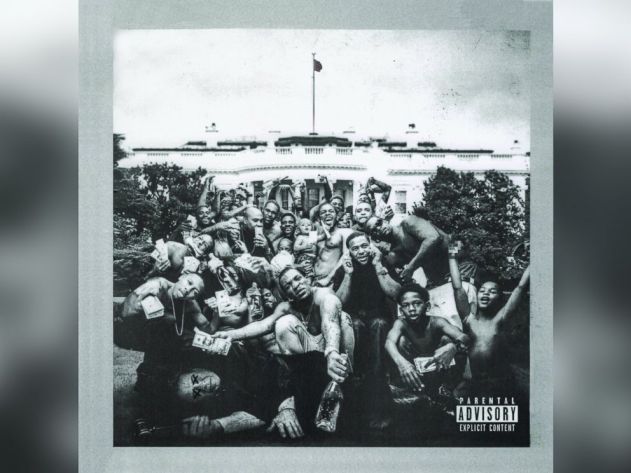

Kendrick Lamar and the Gradual Improvement of White America

Unless you’ve been living in a hyper-productive, internetless void, you’ve noticed the instant, potentially blinded, adulation for Kendrick Lamar’s latest album, To Pimp a Butterfly. Begging the question, how is an album, and in a macro sense an artist, speaking from such a specific point-of-view attaining such incredible acclaim and far-reaching popularity? Now through five front-to-back listens, I’m ready to explore why this might be.

Is it the delivery?

The Beyonce-release, dropping an album unexpectedly without promotion or notice, is here to stay. It has shown to be a knockout success for Beyonce, D’Angelo, Drake and most recently for Kendrick. I don’t know about yours, but my timeline was congested with premature claims of TPAB being a classic album less than an hour from its release. The buzz generated by Kendrick Beyonceing his record can only be classified as a stroke of smooth marketing.

In a world of declining record sales, social buzz is the most valuable commodity a modern artist can possess, and this ploy gave Kendrick droves of it. Releasing the album on a dime gives the consumer an intimate connection with the artist, an immediate shared listening experience with social media at large. Not too mention the financial savings, far less advertising, this mode of delivery gives to the shrinking budgets of major labels. The drawbacks are minimal, the largest being that critics are forced to digest an album and publish a review in a window of about four hours, as opposed to their typical two weeks. But who reads reviews anymore? With streaming, the modern music consumer doesn’t need the music critic. They can listen to the album, for free, and gain their own impression before deciding to purchase the product—whereas in literature and film, customers utilize the critic to decide whether or not they should invest the money to discover their own opinion.

The success of TPAB benefits from the delivery, but it is not a sole reason. Kid Cudi made a release like this with his last album, and the response to that was chilly. It can’t be the release.

Is it a Good Kid, M.A.A.D City hangover?

Good Kid is universally, at least as much as possible in the Twitter era, considered to be a classic album. Released in the post-Drake Hip-Hop climate, Good Kid demonstrated a flawless blend of melody, storytelling, and novel vocal delivery. A concise, thematically-consistent 12-track sonic dream, the album was able to do what few can—shed out monster singles without jeopardizing the album’s individual artistry. Bitch Don’t Kill My Vibe, Swimming Pools, and Money Trees all charted tremendously on their own, yet the when they play in the natural flow of the album, they don’t sound like singles.

Is the urgency in awarding TPAB a classic tag a blinded reaction carried over from Good Kid? I think not.

In music, hip-hop specifically, following up a classic debut album is an impossible burden, not an unfair advantage. Just ask 50 Cent whose follow up to (one of the greatest debut albums in the infancy of hip-hop’s thirty-year history) Get Rich or Die Tryin, The Massacre, was received as a disappointment despite selling over a million records in its first week and receiving a Grammy nomination for Best Album—when Grammy’s were still something to be desired. Or Nas, who after 25 years of attempting to outrun the enormity of the success of his debut album Illmatic, capitulated and, in an unprecedented move, began to tour the quarter-century old record. When his acting jobs finally dry out, look for 50 Cent to do the same.

Though not a debut, Drake was also greeted with a less-than-tepid response for his Nothing Was the Same offering, following the classic-worthy Take Care. When your debut is a classic, we grade everything that follows on its Mt. Everest-level pedestal. So that isn’t the case here.

Is it the Messaging?

When you boil down the sharply structured, speed-variant verses, the Outkast-esque balance of hollow drums, bright horns, and myriad soul-infused backup vocals, TPAB is an album about survivors guilt. A continuation of Good Kid, where Kendrick voices the effects that the constant tugging of gang-culture had on the shaping and developing of himself as a man and an artist. On TPAB, he expresses the guilt and confusion for how he has became famous by narrating the inner-city plight for the consumption of White America.

But what makes the discourse of this album so interesting, and Kendrick in general, is that to Kendrick Lamar, there are two White America’s.

There is the White America who shot Trayvon Martin, who squeezed the life from Eric Garner, who failed to indict the killers of Tamir Rice and Michael Brown, who continue to harbor the nasty, archaic, diseased racism of our ignorant American predecessors. He takes aim at them on one of the album’s richest tracks, Blacker the Berry.

You hate me don’t you? You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture.

Kendrick calls these idiots out, and also rubs their faces with the fact that he, a symbol of their hate, is among the most important artists in popular culture. He is thumbing their noses in the fact that their way of thinking is endangered.

Endangering the racist philosophies of the White America of the past, is the other White America Kendrick Lamar recognizes: the growing class of antiracist whites within leftist White America — and they all seem to love Kendrick Lamar.

Open up a new tab and run a Google-image search of black lives matter.

Welcome back. You noticed it, didn’t you? Many of the images displayed young white Americans, protesting their exhaustion towards the continued mistreatment of black citizens by those entrusted to protect and serve them. Now remember your timeline during the Ferguson protests. Remember the beautiful cross-racial unity of users shouting their discontent for the happenings on their televisions, ashamed and sickened by the actions committed by those of their race in their country. If nothing else, Ferguson showed America that its youth are invested in bettering their future and are unafraid of applying pressure upon their own community: that they are determined to eradicate the racial injustice amidst its community.

Kendrick is aware that a majority of his fans are of this demographic. Though confused by it, he can’t help but notice them at his concerts, or heaping praise upon his Twitter feed.

For a twenty-something white person from the middle class, there is very little to relate to on TPAB. Generally speaking, a majority of people listen to a particular artist because of their relatability to the content. We like Taylor Swift because we’ve all experienced rejection, as she claims to have in her songs. It’s essential that Drake fans know that he is just like them: insecure, introspective, and over-expressive —though of course Drake is a hyper-wealthy, limitlessly famous and ultra-talented version of ourselves. We identify with 2015’s biggest anthem, Know Yourself, because we can envision ourselves having everything, yet still being overwhelmed with stress and longing.

But Kendrick doesn’t cater to his white fans, like his peers do, instead he detours them into his Compton upbringing. As evidence by Hood Politics. A song that features in its chorus the line:

We was in the hood, 14 with the deuce deuce.

This growing element of socially-aware White America doesn’t know a damn thing about being 14-years old, strapped with a pistol. We don’t know anything about Sherm Sticks. Most hadn’t a clue who King Kunta was before hearing Kendricks masterful track. He even nodded to this ignorance by interpolating the Seinfeld theme song, a show that I love, but lets face it, pretty much ignores black people. But the incredible acclaim and far-reaching popularity of this album shows us is that we don’t have to relate to an experience to enjoy and appreciate it.

To Pimp a Butterfly forces the white listener to experience a new, under-served perspective. It forces the white listener to take inventory in their own stereotypes, as Kendrick takes inventory of himself on the introspective, unconventional jam-track “U”. Kendrick questions whether he is doing enough for the betterment of his people. At the same time the white listener examines themselves, realizing that just because you tweet that #BlackLivesMatter doesn’t mean you, the tweeter, are doing enough. But its the recognition of the problem that is the true triumph by Kendrick, and the listener.

We, as a society, still have a long road to defeating racism. Racism is not merely an age thing, as evidenced with the Oklahoma frat scandal last week. But the fact that one of the fraternity brothers recognized the necessity for this hate-filled nonsense to be exposed by filming and leaking the video, shows progress. The pop-level popularity of To Pimp a Butterfly is proof that there is reason to be optimistic about America’s social future.

And that is why we love Kendrick Lamar. That is why we shower him with well-deserved praise.

The Greatest Time of the Year

It’s that time of the year again, the opening weekend of March Madness: the time of year to burn a couple sick days by vegging on the couch for two consecutive days in a buffalo-wing-comatose state, consumed by the ensuing madness and painful decimation of our pursuit of bracket glory!

By why is it that we adore the impending forty-eight hours so?

One would fail to argue that the NCAA product exceeds that of the NBA, as there are numerous idiotic elements the college brand of basketball possesses that their professional counterpart does not: the thirty-five second shot clock that renders the final ninety seconds of play to a festival of fouling ; there is the coaches over-managing the games, being allowed to call time-outs after their team scores; there is the mandatory media time-outs, though placed at the first break in play after the sixteen, twelve, eight and four minute marks, coaches seem to always forget and burn one of their own, forcing situations where the viewers will be slapped with two sets of commercials with just thirty seconds of game time elapsing. Which means in a two-hour game a viewer will see the Sean-Penn-starring-as-Liam-Nielson-in-Taken trailer fifteen times.

Additionally, there is the whole AAU-inlfuenced bit that leaves the players void of fundamental training, incapable of shooting or properly running a pick-and-roll, which gives us 50-47 rock fights. The only NCAA rule that I can discern the NBA should adopt is the one-and-one bonus system. Though the NBA players shoot a much higher percentage from the charity stripe, there is something about the added pressure that leads to more drama in late-game situations. Imagine how fun it would be to watch Lebron shoot a 1-and-1 with twelve seconds left and the Cavs up two?

But even with all these admitted, glaring deficiencies in the college game, we stay in our sweatpants all day and engulf the tournament in large, unchewed, gluttonous bites. So much so that the NCAA tournament TV rights are worth more than the NBA Playoffs and the Super Bowl!

Why do we love it? Certainly it has nothing to do with observing the game at its purest form, as we all know the NCAA is the present-day Costra Nostra.

We love the tournament for the bracket and for what the bracket represents.

We love this month-long tournament because we are obsessed with self-validation.

Our self-validation obsession is best highlighted through the lens of our social media dependency. A tool we use only to broadcast the lives we are living by falsifying the degree in which we are enjoying to live them. If we’re having a night that is a 6-out-of-10, we will throw in some hyperbole to make sure the hundreds of followers, that we don’t really like or know but really care how much they like us, will drown in envy of the fun they’re perceiving that we are having. It’s why we Snapchat bottle service, even though we didn’t buy it, and it’s why we always always always take a picture out of the window of a airplane.

The tournament, more accurately our bracket, serves us as a public display that our sports opinion matters. Sure we might win some scratch if we seize our office/family/friend-group pool, but really we do it for the pride. We watch each of these poorly-played, flaw-riddened games because each one is an examination of how smart we are: we watch to validate our intelligence in relation to the others we know.

And here are my picks, since I, like you, also care too much.

Early Upsets: Dayton wins, Buffalo wins, Davidson wins, Texas and Ohio State. Also Wichita to sweet sixteen.

Elite Eight Picks: Kentucky, Notre Dame, Wisconsin, Arizona, Villanova, Virginia, Utah, Iowa State.

Final Four: Kentucky, Arizona, Virginia, Iowa State

Chipper: Kentucky over Virginia.

Good Luck